Gabriela Feix Pereira* 1, 2, Taiah Rajeh Rosin 2, Bibiana Braga ², Gertrudes Corção1

1 ICBS, Department of Microbiology, UFRGS, Porto Alegre – RS ² Dorf Ketal, Research, Development and Innovation Center, Nova Santa Rita – RS

Abstract

Microbial control in oilfields can be considered a complex subject, since the diversity of the microbiome and the physicochemical characteristics of produced water (PW) yield a unique profile. Biocides are used as microbiological treatment, but the toxicity related to the large volumes used can cause environmental issues. The efficiency of biocides and, consequently, the reduction of environmental impact, can be improved through proper planning. Based on literature information related to biocides, the microorganisms present in PW, and their resistance mechanisms, this article suggests a five-step approach to microbiological treatments: 1) determination of objectives; 2) bioaudit; 3) laboratory selection of biocide(s); 4) selection of viable and representative key performance indicators (KPIs); and 5) treatment monitoring. Finally, this article presents results from a case study aimed at optimizing a microbiological treatment by applying the five-step approach. The results showed an approximately 50% reduction in biocide dosage and system protection for 14 days, compared to 2 days of protection with the previous treatment.

Introduction

Produced water (PW) is the main aqueous waste generated in oilfields, and the increase in oil production over the years has led to even larger volumes being generated (AL-GHOUTI et al., 2019). The volume of PW generated is directly related to the age of the oil reservoir and the extraction method used. In mature wells, the volume of PW can reach nine times the volume of oil extracted. Furthermore, during secondary oil recovery through seawater injection, the volume of PW generated tends to be even higher (JIMÉNEZ et al., 2018).

The management of PW is a critical point, since its variable physicochemical composition and processing and storage conditions drive the development of microorganisms. Sulfate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP) and acid-producing bacteria (APB) are ubiquitous in this environment and are associated with various problems, such as deficiencies in facility integrity and health and safety issues for workers. The SRP group is known mainly for the production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a corrosive and toxic gas (MUYZER; STAMS, 2008). In addition, the release of highly corrosive metabolites by APB also contributes to increased biocorrosion (MARCIALES et al., 2019). Beyond the unique roles of SRP and APB, syntrophic interactions between both groups have been reported (XU; LI; GU, 2016; DAWUDA; TALEB-BERROUANE; KHAN, 2021).

The use of biocides is strongly suggested as a tool for mitigating and preventing microbiological problems. The most widely used biocides globally in the oil industry are glutaraldehyde, 2,2-dibromo-3-nitrilopropionamide (DBNPA), tetrakis(hydroxymethyl)phosphonium sulfate (THPS), and alkyl dimethyl benzyl ammonium chloride (ADBAC) (KAHRILAS et al., 2015). However, poorly planned microbiological treatments can trigger microbial resistance, considerably decreasing treatment effectiveness and increasing environmental damage due to higher biocide dosages driven by loss of efficacy.

Proper planning of microbiological treatment must consider the system’s physicochemical and microbiological variables. In this article, the impact of these variables on treatment is reduced by applying five steps during planning: 1) well-defined objectives; 2) bioaudit for an integrated view of the system; 3) selection of appropriate biocide(s) in the laboratory, considering process conditions and susceptibility of microbial targets; 4) selection of viable and representative KPIs; and 5) treatment monitoring. Finally, this article demonstrates a case study using this five-step approach.

Microbiological composition of PW

Reservoir geology and oil separation processes determine the physicochemical characteristics of PW, and these characteristics select the best-adapted microorganisms. In general, due to extreme conditions, the oilfield microbiome is predominantly composed of bacteria, although the presence of archaea is also frequently reported (SIERRA-GARCIA et al., 2017; HIDALGO et al., 2021).

Due to their negative impact on the oil value chain, some microbial groups are more studied than others. SRP, mainly sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), the most studied group, are directly related to the biological generation of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and have been associated with type I biocorrosion (JIA et al., 2019a; RAJBONGSHI; GOGOI, 2021). The APB group, also called fermentative bacteria, release corrosive metabolic byproducts that can increase type II biocorrosion (JIA et al., 2019a; MARCIALES et al., 2019). Beyond the individual roles of SRB and APB, syntrophic interactions—where SRB use APB metabolic byproducts (e.g., lactate and acetate) as carbon sources—have been reported. Ultimately, these syntrophic interactions confer robustness to biofilm structure. In addition to the syntrophic relationship, another variable during biofilm formation is oxygen tolerance. SRB, strict anaerobes, settle at the base of the biofilm, and due to syntrophic relationships, APB settle in upper layers, since they are more oxygen-tolerant. These heterogeneous structures generate dynamic biocorrosion foci, mixing both type I mechanisms (due to SRB action) and type II (due to APB action), complicating control. Furthermore, thick and heterogeneous biofilms hinder biocide penetration, requiring on average a biocide concentration ten times higher for mitigation compared to planktonic (free-living) bacteria (XU; LI; GU, 2016).

Although less frequently reported, other microbial groups play a role in biocorrosion processes and oil deterioration, such as methanogenic archaea and nitrate-reducing bacteria (NRB) (LAHME et al., 2019; JI et al., 2020). Methanogenic archaea play an important role in hydrocarbon biodegradation due to their ability to oxidize hydrogen in crude oil and other components such as n-alkanes, benzene, toluene, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (RAJBONGSHI; GOGOI, 2021). NRB reduce nitrate to nitrite and can remove existing sulfide or inhibit sulfide production in PW by SRB (RAJBONGSHI; GOGOI, 2021).

Bacterial resistance to biocides

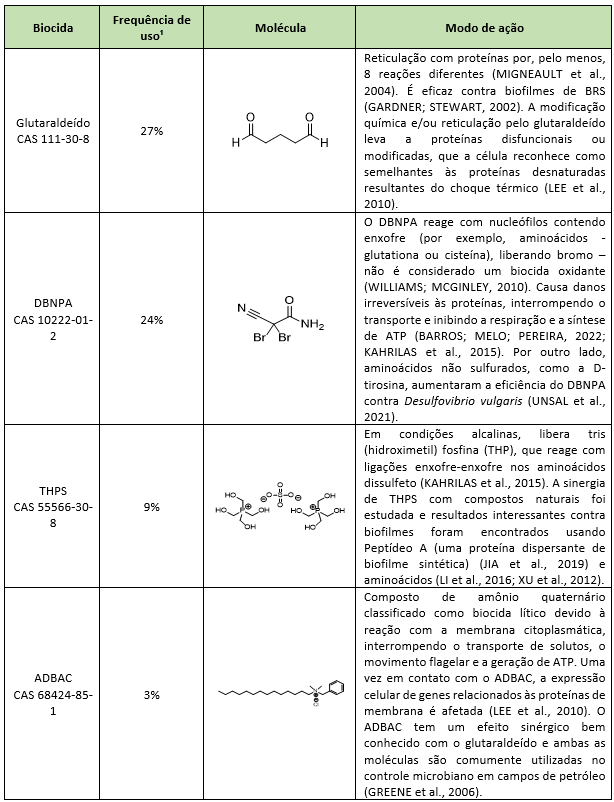

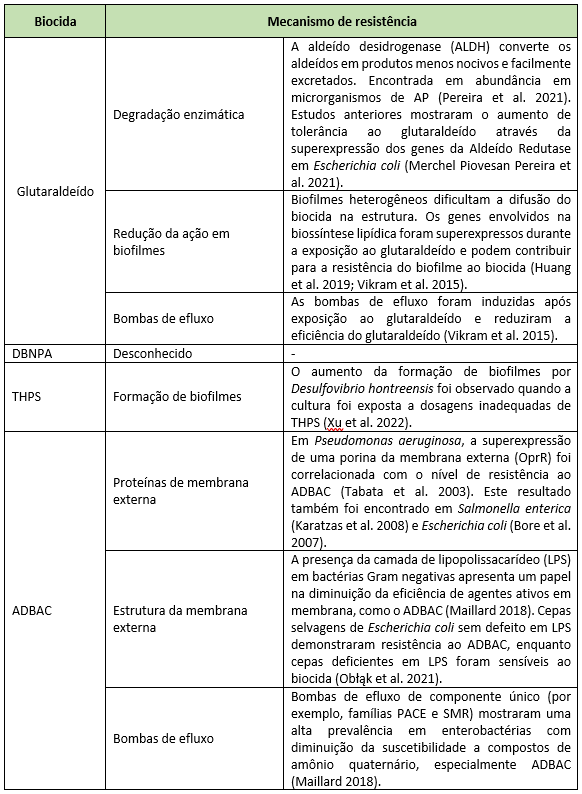

The most common way to mitigate microbial problems in oilfields is the application of biocides. The standard biocides used worldwide in PW, their modes of action, and frequency of use are described in Table 1. The bacterial resistance mechanisms described for these standard biocides are shown in Table 2. Biocides used almost exclusively in oilfields (i.e., THPS and DBNPA) have not had their modes of action and resistance mechanisms fully elucidated due to the lack of available literature. On the other hand, biocides commonly applied in the health and food sectors show a high density of information.

Among the main resistance mechanisms described for biocides are efflux pumps and biofilm formation. Efflux pumps are responsible for reducing the intracellular concentration of toxic molecules in bacterial cells. The AcrAB–TolC and MATE efflux pump families are widely disseminated among bacterial species and can confer reduced susceptibility to a broad variety of biocides, such as quaternary ammonium compounds and glutaraldehyde. Increased expression of efflux pump–related genes has been identified during exposure to biocides, supporting the role of this important resistance mechanism in bacteria (MORENTE et al., 2013; BEDOYA et al., 2021). In addition to efflux pumps, biofilm formation is also an important resistance mechanism, especially in oilfields. Oilfields are highly stressful environments, with limited nutrients and extreme pH and temperatures. These conditions, coupled with the presence of biocides, can trigger morphological responses in bacterial populations that immediately adhere to a surface as a survival strategy. After the adhesion phase, the growth phase can occur in pipelines with low flow rates or storage tanks, where both water and suspended solids settle at the bottom, creating conditions where sessile bacteria are exposed to intermittent cycles of nutrient presence and depletion, resulting in thick biofilms (JENNEMAN; DE LEÓN, 2022).

PW treatment with biocides

The use of biocides to control bacterial growth in oilfields has not been seriously considered. An inadequate biocide treatment can contribute to increased selective pressure and, consequently, bacterial resistance (CAMPA et al., 2019). Thus, the ideal scenario would be the establishment of more specific and better planned treatments.

A case of biocide treatment implementation considering physicochemical and microbiological conditions was previously described. Samples from four different oilfields (two Brazilian and two Argentine) that presented resistance issues with the current treatment (THPS in continuous dosing) were evaluated in the laboratory using molecular and culture-dependent techniques. Laboratory evaluations demonstrated the most efficient combination of biocides and the benefit of changing the application scheme, indicating batch application instead of continuous application. Monitoring was carried out through the concentration of total anaerobic bacteria and, as a result, after the first month all four oilfields achieved a 6-log reduction in bacterial concentration (PASCHOALINO et al., 2019). The results described in this study support the five-step approach detailed in this topic.

Step 1 – Treatment objectives

Several reasons can explain the application of biocides in PW, for example biocorrosion control, H2S reduction, tank and pipeline cleaning, and inhibition or eradication of biofilms in filters. Thus, before starting treatment, it is important to list the problems that can be solved with biocide application and the main microbial targets, in order to outline treatment objectives. Despite the broad spectrum of action of biocides in general, microorganism susceptibility is variable (PEREIRA; PILZ-JUNIOR; CORÇÃO, 2021) and biocide application will hardly affect all groups present in PW to the same extent; therefore, defining the main treatment objective and microbial targets is crucial.

Step 2 – Bioaudit

The bioaudit step aims to investigate the presence of microorganisms along the process and identify critical contamination points. During the assessment, process points with higher concentrations are identified and considered as candidates for biocide injection.

The bioaudit consists of scanning the process using microbiological tools with molecular, enzymatic, or culture-dependent approaches (PASCHOALINO, 2021). Analyses based on culture-dependent techniques are the most used and recommended by industry standards to determine bacterial concentration. Standard NACE TM0194-2014 – Field Monitoring of Bacterial Growth in Oil and Gas Systems, for example, describes the method and culture media for SRB enumeration and other bacterial groups. API-RP-38 – Recommended Practice for Biological Analysis of Subsurface Injection Waters also recommends different culture media for bacterial enumeration.

In practice, these analyses may need to be complemented with molecular, culture-independent methods, since it is known that at least 90% of microorganisms found in oilfields are not culturable (SKOVHUS; WHITBY, 2019). One study evaluated by 16S rRNA the microbial composition of an injection water sample and of the bacterial consortium grown in culture medium originating from this sample. The results showed that the dynamics of the microbial population changed in both cases, affecting responses to biocides (ROMERO et al., 2005).

Despite cost disadvantages, the use of molecular methods can be crucial in defining biocide treatment targets. Several studies report the use of 16S rRNA gene sequencing to assess microbiome diversity in oilfields (KEASLER et al., 2013; LI et al., 2017; HIDALGO et al., 2021). Another important molecular tool in this field is Real-Time PCR (RTPCR), which uses primers to quantify specific genes and correlate them with microorganisms present in the sample. With this same tool, the expression of resistance genes, which can affect microbiological treatment efficacy, can also be evaluated (CAMPA et al., 2019).

Enzymatic tools can also be used in the bioaudit step. ATP quantification provides data on the total concentration of viable cells in the sample (HAMMES et al., 2010). Although it is not indicated as a stand-alone tool due to the broad scope of the response—considering not only microorganisms, but any viable cell present in the sample—it can be used as a complementary technique.

Step 3 – Laboratory screening of biocides

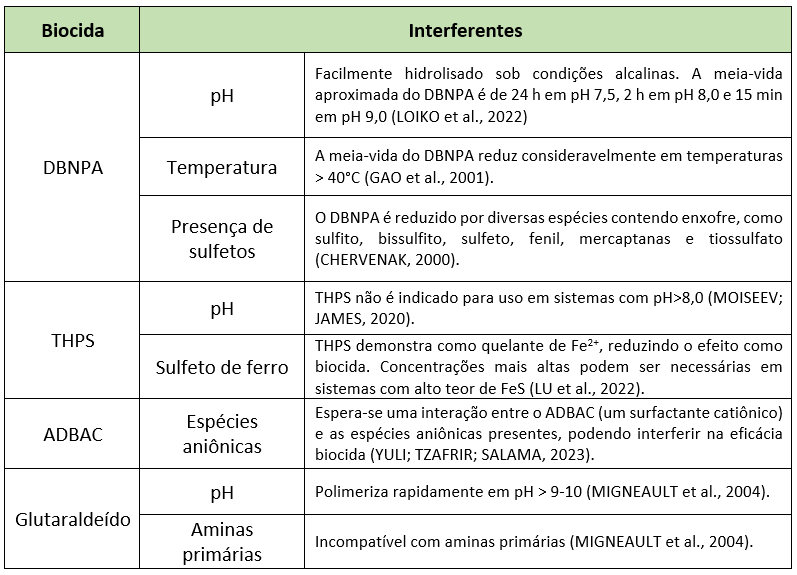

In addition to microbiological composition, the physicochemical data from candidate injection points must also be considered before biocide screening, since the chemical stability of synthetic biocides can be impaired by conditions such as pH, temperature, and the presence of reactive chemicals (Williams and Schultz 2015). Table 3 shows the main known interferents affecting the chemical stability of biocides. Considering chemical stability, this step aims to find the most efficient biocides under the system conditions.

The standard methods mentioned in step 2 (item 3.2.) can also be used in the screening step to determine the susceptibility of planktonic bacteria to biocides. For evaluating biocide efficiency in biofilms, NACE TM21495 – Laboratory Evaluation of the Effect of Biocides on Biofilms addresses laboratory evaluation protocols based on culture media (WADE et al., 2023). In addition, biofilms can be assessed through growth in 96-well microplates and read by spectrophotometry (STEPANOVIĆ et al., 2007), or on metal coupons with quantification by Most Probable Number (MPN) (JIA et al., 2017; WANG et al., 2022).

Step 4 – Selection of Key Performance Indicators (KPI)

KPIs are used to quantify the effectiveness of microbiological treatment (JOHNSON, 2017; KEASLER et al., 2017), and their proper use is one of the keys to effective treatment (JIANG et al., 2021). KPI selection depends on the objectives defined for the treatment (step 1; item 3.1.), on the microbial targets (step 2; item 3.2.), and on the selected biocides (step 3; item 3.3.). This study classified KPIs into direct and indirect approaches. Direct KPIs refer directly to data related to microbial growth and biocides. Examples of direct KPIs are the concentration of planktonic or sessile cells in the systems and residual biocide content. Indirect KPIs are related to system integrity and physicochemical data, for example, corrosion rates, H2S content, pressure in pipelines, and water filters.

Step 5 – Treatment monitoring

It is essential that the tools selected for KPI monitoring are viable for use in oilfields, considering the available infrastructure. Monitoring the selected KPIs supports decision-making related to treatment (JOHNSON, 2017). Methods for monitoring direct KPIs can range from culture-dependent to molecular techniques (PASCHOALINO, 2021); examples were described in step 2 (item 3.2.). As for indirect KPIs, H2S content can be monitored using titration methods (NASSER et al., 2021), and corrosion rates can be monitored by metal coupons installed along the system, electrical resistance probes, linear polarization instruments, or equivalent methods (AL-JANABI, 2020). In addition, process follow-up data such as pressure, flow rate, and others can be used as KPIs.

Case study

In addition to the optimization of microbiological treatment described by Paschoalino et al. 2019 in onshore fields, the optimization of a biocide treatment on a Brazilian offshore platform was carried out by Dorf Ketal Brasil Ltda. The platform was located in the Pre-Salt layer of the Santos Basin, in a water depth of about 2,240 m.

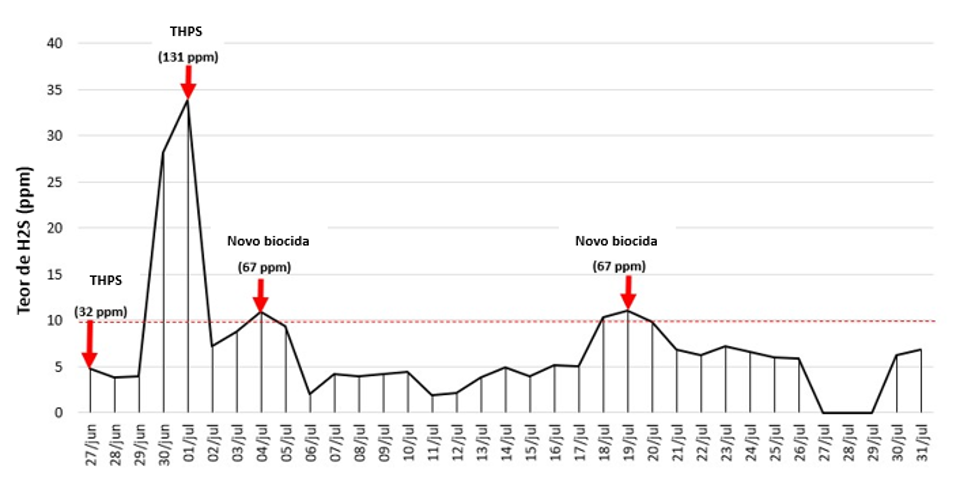

Before optimization, the biocide THPS was applied to the slop tank twice a week at a concentration of approximately 130 ppm per batch. The tank had a thick oil layer on the surface, which hindered THPS from reaching the water. Moreover, due to the rapid degradation of the molecule, no long-term efficiency was observed, resulting in the need to increase the application frequency.

The main objective of applying a microbiological treatment in the slop tank was to control H2S generation, and the objective of optimizing the treatment was to reduce the frequency of biocide application. As the microbial target, SRB were established due to their role in H2S generation. Tank water samples were sent to the Dorf Ketal laboratory and, based on the history of resistance to THPS, the microbial target, and the physicochemical conditions of the water, a customized biocide was developed.

After laboratory development, a field trial was carried out to define the biocide concentration and application frequency in the slop tank (Fig. 1). The H2S concentration in water was used as an indirect KPI for monitoring, and the acceptable H2S concentration limit was 10 ppm. In addition to monitoring H2S content, ATP concentration was used as a direct KPI.

As a result, optimization led to H2S control for 14 days with half the concentration (67 ppm) compared to the previously used THPS (131 ppm). Microbial control efficiency, quantified by ATP concentration, reached 89% with the optimized treatment (data not shown).

Conclusions

Focusing on optimizing microbial control and reducing the interference of physicochemical and microbiological variables, this article suggests a five-step approach to microbiological treatments. Treatment objectives should be clear before planning, and a bioaudit is desirable to understand microbiome composition and select precise microbial targets. After selecting microbial targets, laboratory screening of biocides can demonstrate which biocides are suitable considering their efficiency and chemical stability. Finally, representative KPIs according to treatment objectives can be monitored through several techniques described in this article. In a case study, using the five-step approach resulted in reducing the frequency of biocide application in the slop tank of a platform located in the Brazilian Pre-Salt. Optimization resulted in 14 days of H2S control using the customized treatment, with a dosage 50% lower compared to the previously used biocide (THPS).

References

jection SystemCORROSION 2020, 14 jun. 2020. .

AL-GHOUTI, M. A. et al. Produced water characteristics, treatment and reuse: A reviewJournal of Water Process Engineering, 2019. .

AL-JANABI, Y. T. An overview of corrosion in oil and gas industry: upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors. Corrosion Inhibitors in the Oil and Gas Industry, p. 1–39, 2020.

BARROS, A. C.; MELO, L. F.; PEREIRA, A. A Multi-Purpose Approach to the Mechanisms of Action of Two Biocides (Benzalkonium Chloride and Dibromonitrilopropionamide): Discussion of Pseudomonas fluorescens’ Viability and Death. Frontiers in Microbiology, v. 13, p. 842414, 2022.

BEDOYA, K. et al. Assessment of the microbial community and biocide resistance profile in production and injection waters from an Andean oil reservoir in Colombia. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 157, p. 105137, 2021. Disponível em: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964830520310684>.

BORE, E. et al. Adapted tolerance to benzalkonium chloride in Escherichia coli K-12 studied by transcriptome and proteome analyses. Microbiology, v. 153, n. 4, p. 935–946, 2007.

CAMPA, M. F. et al. Unconventional oil and gas energy systems: an unidentified hotspot of antimicrobial resistance? Frontiers in microbiology, v. 10, p. 2392, 2019.

CHERVENAK, M. C. The environmental fate of commonly used oxidizing and non-oxidizing biocides: reactions of industrial water biocides within the system. In: Int Environ Conf Exhibit, Anais…Citeseer, 2000.

DAWUDA, A.-W.; TALEB-BERROUANE, M.; KHAN, F. A probabilistic model to estimate microbiologically influenced corrosion rate. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, v. 148, p. 908–926, 2021.

EL-AZIZI, M.; FARAG, N.; KHARDORI, N. Efficacy of selected biocides in the decontamination of common nosocomial bacterial pathogens in biofilm and planktonic forms. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases, v. 47, p. 60–71, 2016.

GAO, Y. et al. Efficacy of DBNPA against Legionella pneumophila: experimental results in a model water system. ASHRAE Transactions, v. 107, p. 184, 2001.

GARDNER, L. R.; STEWART, P. S. Action of glutaraldehyde and nitrite against sulfate-reducing bacterial biofilms. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, v. 29, n. 6, p. 354–360, 1 dez. 2002. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jim.7000284>.

GREENE, E. A. et al. Synergistic inhibition of microbial sulfide production by combinations of the metabolic inhibitor nitrite and biocides. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006.

HIDALGO, K. J. et al. Genome-Resolved Meta-Analysis of the Microbiome in Oil Reservoirs WorldwideMicroorganisms , 2021. .

HUANG, L. et al. Role of LptD in Resistance to Glutaraldehyde and Pathogenicity in Riemerella anatipestifer Frontiers in Microbiology , 2019. . Disponível em: <https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01443>.

JENNEMAN, G. E.; DE LEΌN, K. B. Environmental stressors alter the susceptibility of microorganisms to biocides in upstream oil and gas systems. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 169, p. 105385, 2022.

JI, J.-H. et al. Methanogenic biodegradation of C13 and C14 n-alkanes activated by addition to fumarate. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 153, p. 104994, 2020.

JIA, R. et al. Laboratory testing of enhanced biocide mitigation of an oilfield biofilm and its microbiologically influenced corrosion of carbon steel in the presence of oilfield chemicals. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 125, p. 116–124, 2017. Disponível em: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964830517308508>.

JIA, R. et al. Microbiologically influenced corrosion and current mitigation strategies: A state of the art reviewInternational Biodeterioration and Biodegradation, 2019a. .

JIA, R. et al. A sea anemone-inspired small synthetic peptide at sub-ppm concentrations enhanced biofilm mitigation. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 139, p. 78–85, 2019b. Disponível em: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964830518307637>.

JIANG, W. et al. A critical review of analytical methods for comprehensive characterization of produced water. Water, v. 13, n. 2, p. 183, 2021.

JIMÉNEZ, S. et al. State of the art of produced water treatmentChemosphere, 2018. .

JOHNSON, R. J. Combining Advanced Biocide Evaluation and Microbial Monitoring to Optimise Microbial Control. In: SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry, Anais…OnePetro, 2017.

KAHRILAS, G. A. et al. Biocides in Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids: A Critical Review of Their Usage, Mobility, Degradation, and Toxicity. Environmental Science & Technology, v. 49, n. 1, p. 16–32, 6 jan. 2015. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.1021/es503724k>.

KARATZAS, K. A. G. et al. Phenotypic and proteomic characterization of multiply antibiotic-resistant variants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium selected following exposure to disinfectants. Applied and environmental microbiology, v. 74, n. 5, p. 1508–1516, 2008.

KEASLER, V. et al. Expanding the microbial monitoring toolkit: Evaluation of traditional and molecular monitoring methods. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 81, p. 51–56, 2013.

KEASLER, V. et al. Biocides overview and applications in petroleum microbiology. Trends in oil and gas corrosion research and technologies, p. 539–562, 2017.

LAHME, S. et al. Metabolites of an oil field sulfide-oxidizing, nitrate-reducing Sulfurimonas sp. cause severe corrosion. Applied and environmental microbiology, v. 85, n. 3, p. e01891-18, 2019.

LEE, M. H. P. et al. Effects of biocides on gene expression in the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2010.

LI, X.-X. et al. Microbiota and their affiliation with physiochemical characteristics of different subsurface petroleum reservoirs. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 120, p. 170–185, 2017.

LI, Y. et al. Enhanced biocide mitigation of field biofilm consortia by a mixture of D-amino acids. Frontiers in microbiology, v. 7, p. 896, 2016.

LOIKO, N. et al. Biocides with Controlled Degradation for Environmentally Friendly and Cost-Effective Fecal Sludge Management. Biology, v. 12, n. 1, p. 45, 2022.

LU, H. et al. FeS Scale Control and Prevention in Water Injection Systems. In: SPE International Oilfield Scale Conference and Exhibition, Anais…OnePetro, 2022.

MAILLARD, J.-Y. Resistance of bacteria to biocides. Microbiology spectrum, v. 6, n. 2, p. 2–6, 2018.

MARCIALES, A. et al. Mechanistic microbiologically influenced corrosion modeling—A reviewCorrosion Science, 2019. .

MERCHEL PIOVESAN PEREIRA, B. et al. Tolerance to Glutaraldehyde in Escherichia coli Mediated by Overexpression of the Aldehyde Reductase YqhD by YqhC Frontiers in Microbiology , 2021. . Disponível em: <https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2021.680553>.

MIGNEAULT, I. et al. Glutaraldehyde: behavior in aqueous solution, reaction with proteins, and application to enzyme crosslinking. Biotechniques, v. 37, n. 5, p. 790–802, 2004.

MOISEEV, D. V; JAMES, B. R. Tetrakis (hydroxymethyl) phosphonium salts: Their properties, hazards and toxicities. Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Silicon and the Related Elements, v. 195, n. 4, p. 263–279, 2020.

MORENTE, E. O. et al. Biocide tolerance in bacteria. International journal of food microbiology, v. 162, n. 1, p. 13–25, 2013.

MUYZER, G.; STAMS, A. J. M. The ecology and biotechnology of sulphate-reducing bacteriaNature Reviews Microbiology, 2008. .

NASSER, B. et al. Characterization of microbiologically influenced corrosion by comprehensive metagenomic analysis of an inland oil field. Gene, v. 774, p. 145425, 2021.

OBŁĄK, E.; FUTOMA-KOŁOCH, B.; WIECZYŃSKA, A. Biological activity of quaternary ammonium salts and resistance of microorganisms to these compounds. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, v. 37, n. 2, p. 22, 2021. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-020-02978-0>.

PAIJENS, C. et al. Determination of 18 biocides in both the dissolved and particulate fractions of urban and surface waters by HPLC-MS/MS. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution, v. 231, n. 5, p. 210, 2020.

PASCHOALINO, M. et al. Evaluation of a glutaraldehyde/THNM combination for microbial control in four conventional oilfields. In: SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry, Anais…OnePetro, 2019.

PASCHOALINO, M. Influence of Chemical Treatments and Topside Processes on the Dominant Microbial Communities at Conventional Oilfields. In: Microbial Bioinformatics in the Oil and Gas Industry. [s.l.] CRC Press, 2021. p. 81–97.

PEREIRA, G. F.; PILZ-JUNIOR, H. L.; CORÇÃO, G. The impact of bacterial diversity on resistance to biocides in oilfields. Scientific reports, v. 11, n. 1, p. 1–12, 2021.

RAJBONGSHI, A.; GOGOI, S. B. A review on anaerobic microorganisms isolated from oil reservoirs. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, v. 37, n. 7, p. 1–19, 2021.

ROMERO, J. M. et al. Genetic Monitoring of Bacterial Populations in a Sea Water Injection System, Identification of Biocide Resistant Bacteria and Study of their Corrosive Effect. In: CORROSION 2005, Anais…OnePetro, 2005.

SAUER, K. et al. Neutral super-oxidised solutions are effective in killing P. aeruginosa biofilms. Biofouling, v. 25, n. 1, p. 45–54, 2009.

SIERRA-GARCIA, I. N. et al. Microbial diversity in degraded and non-degraded petroleum samples and comparison across oil reservoirs at local and global scales. Extremophiles, v. 21, n. 1, p. 211–229, 2017.

SKOVHUS, T. L.; WHITBY, C. Oilfield Microbiology. [s.l.] CRC Press, 2019.

STEPANOVIĆ, S. et al. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. Apmis, v. 115, n. 8, p. 891–899, 2007.

TABATA, A. et al. Correlation between resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to quaternary ammonium compounds and expression of outer membrane protein OprR. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, v. 47, n. 7, p. 2093–2099, 2003.

UNSAL, T. et al. Assessment of 2, 2-Dibromo-3-Nitrilopropionamide Biocide Enhanced by D-Tyrosine against Zinc Corrosion by a Sulfate Reducing Bacterium. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, v. 60, n. 10, p. 4009–4018, 2021.

VIKRAM, A.; BOMBERGER, J. M.; BIBBY, K. J. Efflux as a glutaraldehyde resistance mechanism in Pseudomonas fluorescens and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2015.

WADE, S. A. et al. The role of standards in biofilm research and industry innovation. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, v. 177, p. 105532, 2023. Disponível em: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0964830522001603>.

WANG, D. et al. Mitigation of carbon steel biocorrosion using a green biocide enhanced by a nature-mimicking anti-biofilm peptide in a flow loop. Bioresources and Bioprocessing, v. 9, n. 1, p. 67, 2022. Disponível em: <https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-022-00553-z>.

WILLIAMS, T. M.; MCGINLEY, H. R. Deactivation of industrial water treatment biocides. In: CORROSION 2010, Anais…OnePetro, 2010.

XU, D. et al. D-amino acids for the enhancement of a binary biocide cocktail consisting of THPS and EDDS against an SRB biofilm. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, v. 28, n. 4, p. 1641–1646, 2012.

XU, D.; LI, Y.; GU, T. Mechanistic modeling of biocorrosion caused by biofilms of sulfate reducing bacteria and acid producing bacteria. Bioelectrochemistry, 2016.

XU, L. et al. Inadequate dosing of THPS treatment increases microbially influenced corrosion of pipeline steel by inducing biofilm growth of Desulfovibrio hontreensis SY-21. Bioelectrochemistry, p. 108048, 2022. Disponível em: <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S156753942100311X>.

YULI, I.; TZAFRIR, I.; SALAMA, P. Compatibility Investigation of Cationic Surfactants with Anionic Species. Cosmetics, v. 10, n. 2, p. 45, 2023.

___________________________________________________

___________________________________________________