Bibiana Braga1, Maylline Gomes2, Rubens Bisatto3,

Rita Cristina da Silva4, Mahesh Subramaniyam5

1 Master’s in Chemistry – DORF KETAL

2 Oil & Gas Technologist – DORF KETAL

3 Ph.D., Industrial Chemist – DORF KETAL

4 Ph.D., Industrial Chemistry – DORF KETAL

5 Ph.D., Chemist – DORF KETAL

Abstract

Scale inhibitors are widely used to prevent salt deposition in pipelines. Among the various chemical classes of these products, sulfonated polycarboxylates stand out; in addition to other advantages, they have higher thermal stability when compared with phosphonates and aminophosphonates. With new application challenges featuring increasingly higher temperatures and pressures, such as those in the Brazilian pre-salt, there is a growing search for scale inhibitor products that offer the same advantages as sulfonated polycarboxylates. This work presents a series of laboratory development and flow assurance application tests to evaluate three different chemical bases of scale inhibitors under realistic pre-salt scenarios. To this end, a comparison was made between a phosphonate molecule and two developed polymers (a sulfonated copolymer and a sulfonated terpolymer) regarding their compatibility with three different types of brines, static efficiency, dynamic efficiency, and applicability in subsea systems.

Introduction

The deposition of inorganic salts in pipelines is commonly observed in oil production processes. Such scale can reduce well productivity by restricting the flow of gas and oil, in addition to increasing wear of pipelines and equipment.

One of today’s challenges is to develop products that meet pre-salt conditions for oil production, where extreme temperature, pressure, and salinity are found (above 120°C, greater than 500 psi, and above 200,000 ppm, respectively).

The onset of scaling is associated with changes in the physical conditions of fluids, such as variations in brine temperature, pressure, and pH; the degree of water saturation; the presence of impurities; and contact between formation water and seawater (rich in sulfates). Salt deposition may also arise from interaction with other chemical agents used in treatment.1, 2

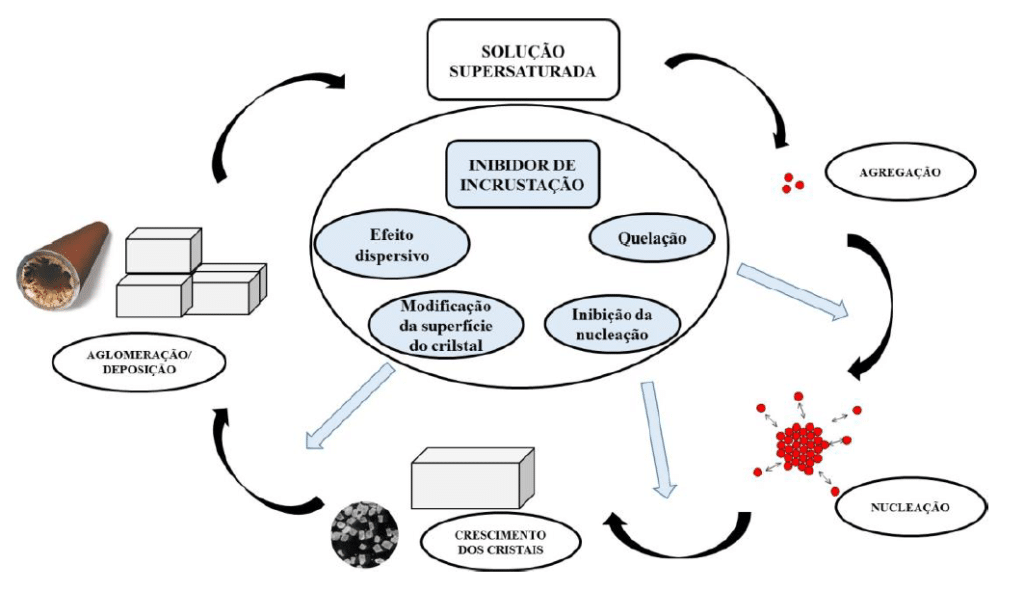

For salt deposition in pipelines—if there is brine supersaturation or physical conditions conducive to such a phenomenon—the first step in scale formation is aggregation of particles that will induce nucleation. Next, crystal growth occurs until it reaches a sufficient size to adhere to the pipelines. A schematic diagram can be seen in Figure 1.

One of the main ways to combat scaling in pipelines is through the use of chemical agents. Among these, anti-scale products stand out; they are dosed continuously into oil production lines or via squeeze directly into the oil reservoir.

With respect to scale inhibition mechanisms, one can highlight nucleation inhibition, retardation of crystal growth, and dispersive effect.3,4

Nucleation inhibition is associated with disrupting the thermodynamic stability that favors crystal growth. The mechanism involves endothermic adsorption of the scale inhibitor onto aggregate particles (chelating property), hindering the nucleation step.3,4

The mechanism related to retarding crystal growth involves irreversible adsorption of the scale inhibitor onto active sites of the forming crystal, blocking them, which delays crystal growth or induces irregularity in the forming structure. At this stage, some scale inhibitors may induce the formation of less stable crystalline structures. Such an example is observed in calcium carbonate scaling, where vaterite and aragonite (less stable and more water-soluble crystalline forms) can be induced to form instead of calcite.5,6

The dispersive effect of anti-scale agents is observed in polymers that present sulfonic groups, which favor dispersion and removal of salts; this effect can be maximized by flow.5,6

Among anti-scale agents used, molecules with phosphonate and aminophosphonate groups and macromolecules based on sulfonated polycarboxylates are noteworthy. Examples of phosphonates and aminophosphonates include ATMP (aminotris(methylenephosphonic) acid), HEDP (1-hydroxyethane-1,1-diphosphonic acid), DTPMP (diethylenetriaminepenta(methylenephosphonic) acid), among others. They are indicated mainly for calcium carbonate scaling, but can act effectively in inhibiting sulfate scaling depending on the medium conditions. These phosphonate- and aminophosphonate-based molecules are less effective at inhibiting the early nucleation stages; however, they act efficiently in inhibiting scaling by binding to active sites of developing nuclei, hindering the formation of stable crystalline structures.3,4 Nevertheless, they present limitations regarding thermal stability, limited tolerance to high–total dissolved solids (TDS) brines (such as pre-salt brines), and low compatibility with other chemicals (such as H₂S scavengers and alcohols).

Sulfonated polycarboxylates are widely discussed in the literature for inhibiting scales such as: calcite, barite, celestite, anhydrite, among others.7,8 The advantage of using this class of scale inhibitors lies in the fact that these molecules act at different stages of crystal growth, i.e., they act from nucleation inhibition to inhibition/retardation of crystal growth, in addition to inhibition through the dispersive effect.4,5,6 Another advantage of using sulfonated polycarboxylates is their thermal stability, which is superior to phosphonate- and aminophosphonate-based scale inhibitors.

Depending on the monomeric composition used, sulfonated polycarboxylates can exhibit excellent tolerance to high-TDS brines, in addition to good compatibility with other chemicals, such as ethanol and H₂S scavengers (products widely used in oil production processes), among others. This is a current need in the Production and Exploration field, whether due to logistics or infrastructure issues, where the search for versatile products—both in effective scale control and in compatibility with different subsea injection products—can reduce facility costs.

Thus, this work aims to evaluate both the scale inhibition capacity of sulfonated polycarboxylate polymers and their compatibility with solvents in three different scenarios of Brazilian pre-salt brines, whose major issue associated with their produced water is the precipitation of calcium and strontium salts under standardized conditions close to those of the pre-salt. In addition, the work also presents the efficiency of these polymeric inhibitors in the presence of 500 ppm and 1,000 ppm of a non-nitrogenated H₂S scavenger typically used in pre-salt wells and conducts a test protocol that certifies the integrity of umbilical lines through which the products must be injected.

Chemical compatibility

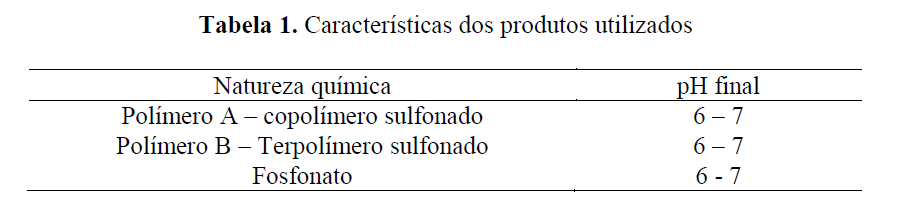

Three products from different chemical families were compared in order to study their applicability in Brazilian pre-salt fields. The characteristics of the bases tested are as follows:

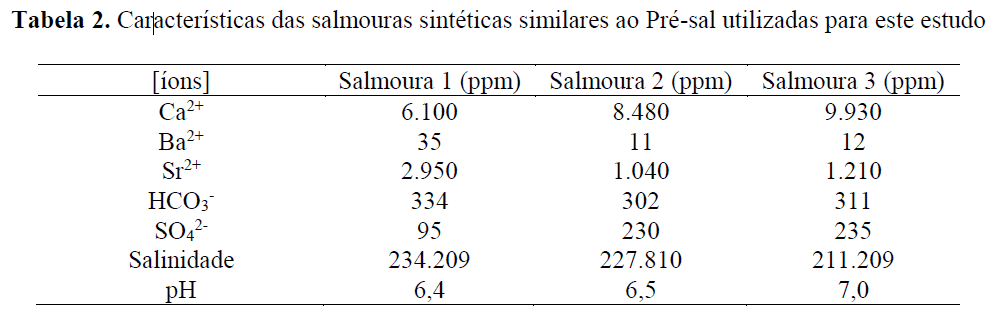

Chemical compatibility between the product and the brine is carried out to assess tolerance mainly to calcium ions present in formation water. In this study, three distinct pre-salt brines were used, whose main characteristics are as follows:

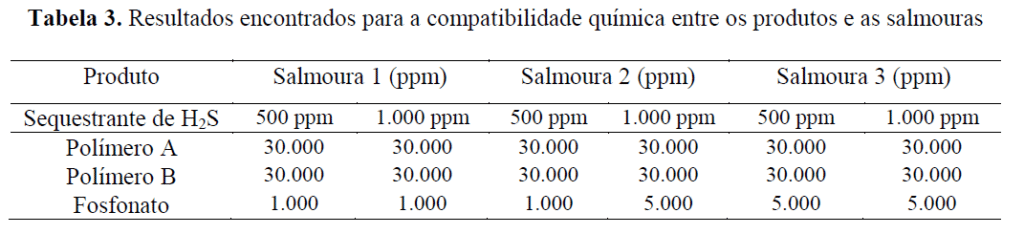

By simulating similar temperature and pressure conditions (T = 120°C and P = 1,000 psi), it was found that the scaling tendency of the brines is, for Brines 1, 2, and 3, respectively, strontium sulfate, barium sulfate, and calcium carbonate. After 24 hours of tests at 120°C—where the products were added at different concentrations to synthetic brines in the absence of scaling anions and in the presence of 500 ppm and 1,000 ppm of the non-nitrogenated H₂S scavenger—the following results were obtained:

As expected, the concentration range in which the phosphonate is compatible is much more restricted than that of the polymeric products. It can be seen that Polymer A and Polymer B exhibit compatibility across the entire range tested (up to 30,000 ppm of product). It is also noted that there is a positive synergy between the phosphonate used and the non-nitrogenated H₂S scavenger, because for Brine 2, an increase in the product’s compatibility limit can be observed with a higher dosage of the H₂S scavenger.

Static Efficiency

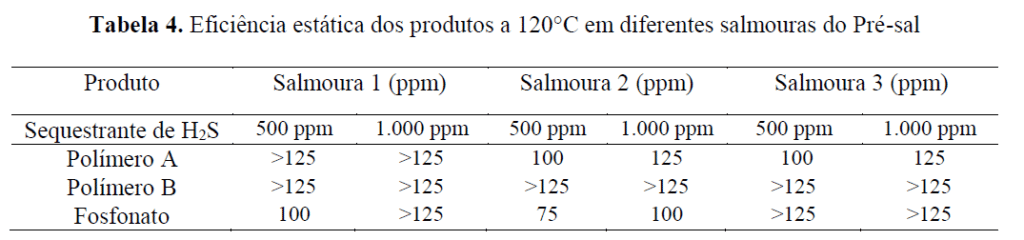

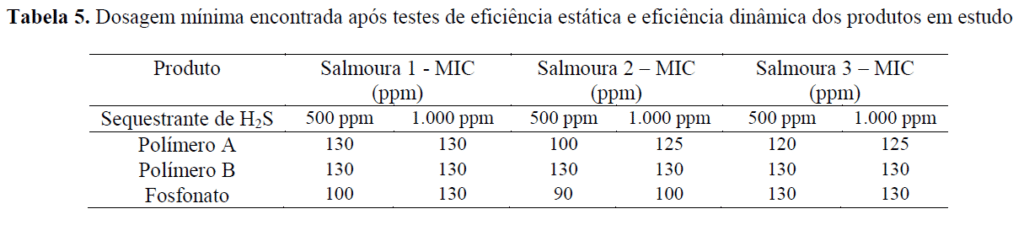

The evaluation of static efficiency was performed visually, confirming product effectiveness at the concentration at which it does not show precipitation after 24 hours at 120°C, in the presence of 500 ppm and 1,000 ppm of H₂S scavenger up to 125 ppm. For this specific condition, an approximate efficiency was found as presented in the table below:

Given that Brine 1 has a scaling tendency at this temperature related to strontium sulfate precipitation, it can be seen that the most efficient product is the phosphonate, which can prevent precipitation at a concentration of 100 ppm when using 500 ppm of H₂S scavenger. For higher concentrations of this product, more scale inhibitor is required to maintain efficiency. For Brine 2, which tends to precipitate barium sulfate, a lower dosage of phosphonate is again needed compared with Polymer A (sulfonated copolymer), and even lower when compared with Polymer B (sulfonated terpolymer), which was not determined. For issues related to calcium carbonate, Polymer A proved more efficient, requiring lower dosages than the other two products.

Dynamic Efficiency

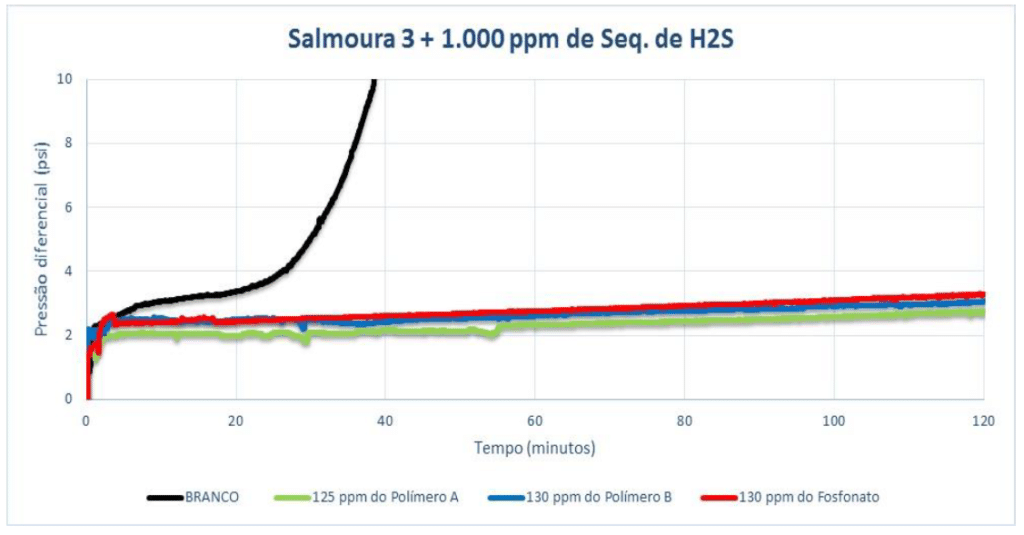

The dynamic inhibition test was carried out at 120°C and a pressure of 1,000 psi in the presence of 500 ppm and 1,000 ppm of H₂S scavenger. This was performed in a DSL (Dynamic Scale Loop). The equipment used has a working coil 1 m in length and 0.5 mm in diameter.

The product is considered approved for this application at the minimum dosage (denoted MIC) when it presents a pressure differential of less than 1 psi during the test time. The test duration is determined from the time the blank takes to scale the equipment (to reach a pressure differential of 4 psi from the established baseline). The run is performed considering 3 times the time the blank took to block the capillary. The brine pH is occasionally modified from the original (increased) when the time the blank takes to cause scaling exceeds 30 minutes. This is done so that, at laboratory scale, the acceptance criterion for product approval can be met (3 times the blank scaling time).

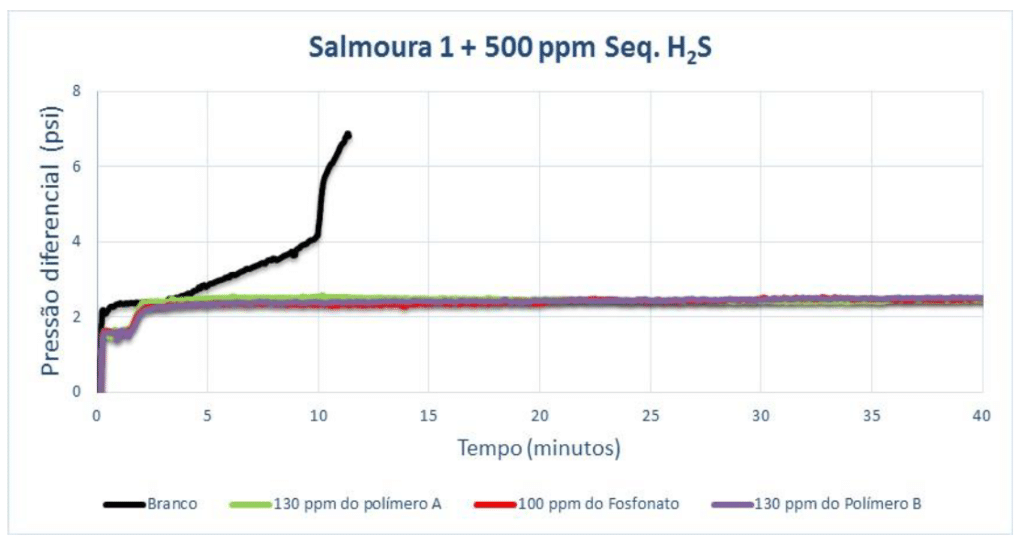

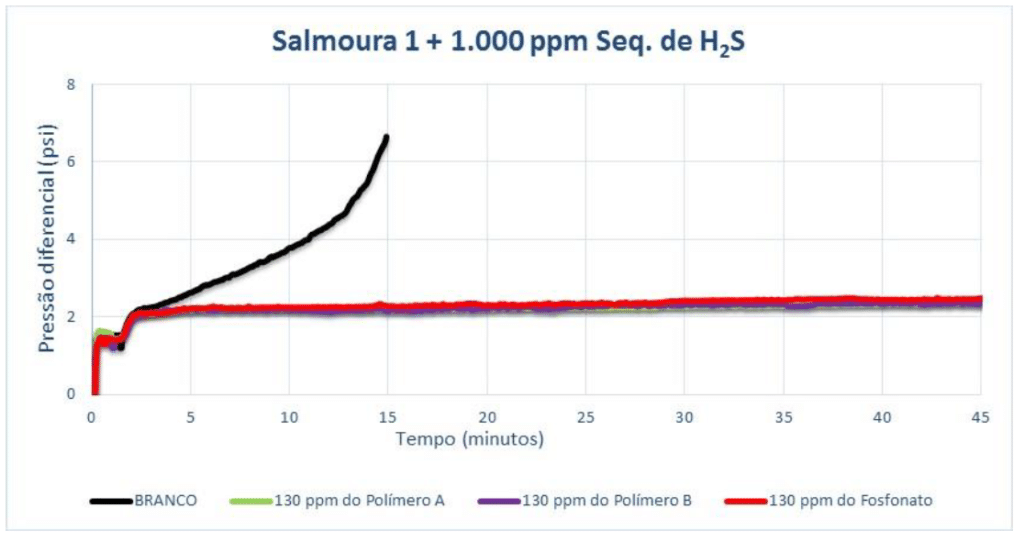

For Brine 1, the pH was adjusted to 8 in order to scale the blank more quickly. The test where 500 ppm of H₂S scavenger was added is shown below:

With 1,000 ppm of H₂S scavenger, the results are shown below. It can be seen that there is a slight improvement in salt precipitation conditions in the presence of a higher dosage of H₂S scavenger. This is evidenced by the longer blank scaling time.

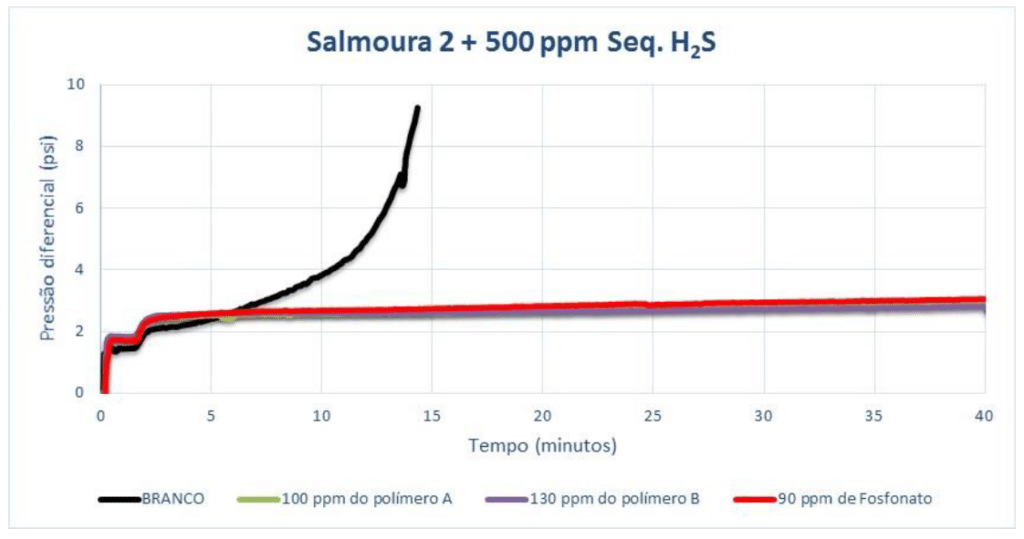

Brine 2 was adjusted to pH 8 so that the blank scaling time would be more suitable for laboratory-scale tests. Adding 500 ppm of H₂S scavenger, the minimum dosage for Polymer A is 100 ppm, while for Polymer B it is 130 ppm. The lowest MIC value is for the phosphonate product.

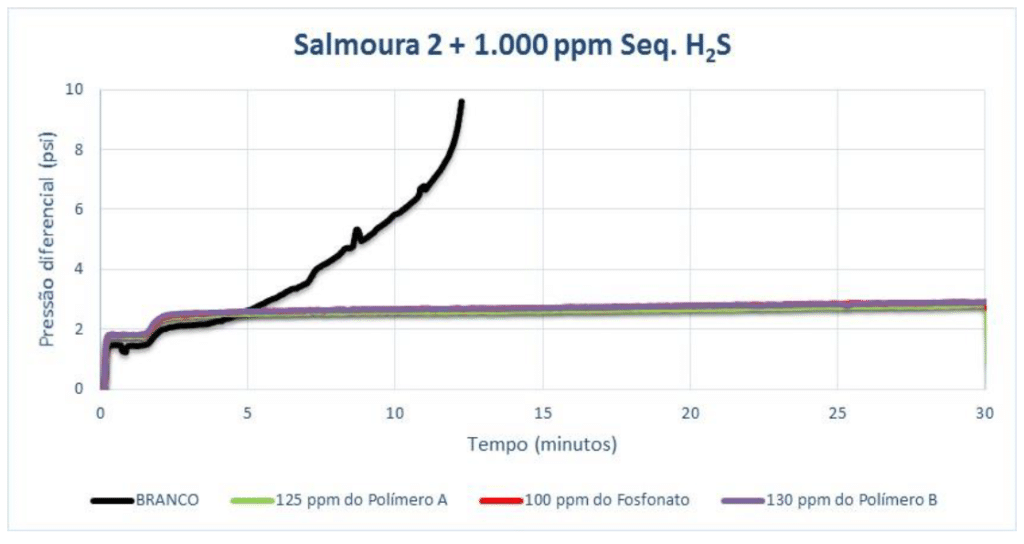

Adding 1,000 ppm of H₂S scavenger to Brine 2, the following MIC values were found:

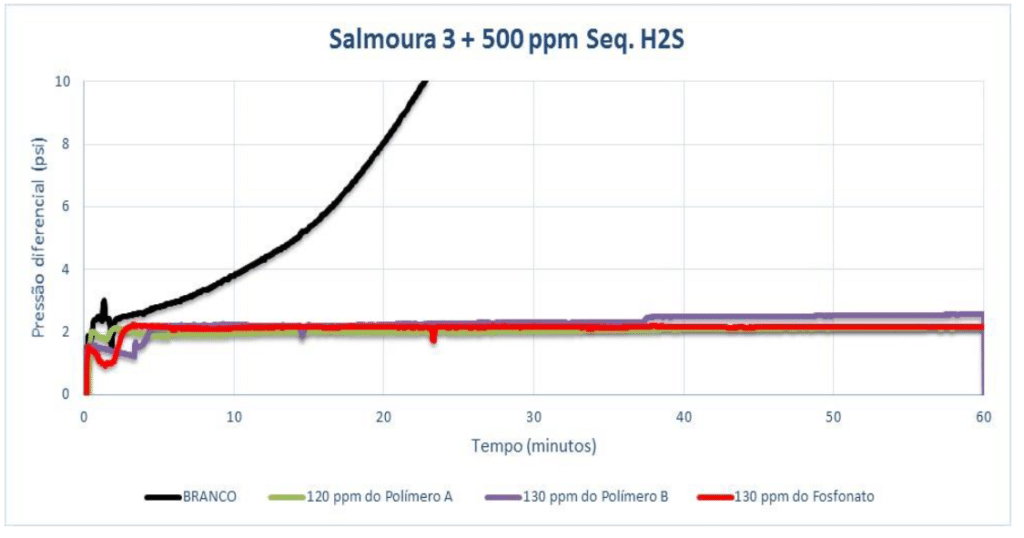

For Brine 3 with 500 ppm of H₂S scavenger, it was necessary to increase the pH to 7.5 for scaling to occur. Polymer A showed efficiency at 120 ppm, and Polymer B and the phosphonate at 130 ppm.

For Brine 3 with 1,000 ppm of H₂S scavenger (pH 7.5), Polymer A showed efficiency at 125 ppm (dosage indicated by static efficiency). Polymer B and the phosphonate were tested at a dosage greater than 125 ppm, as also indicated in the previous test, and both showed efficiency at 130 ppm. After 120 minutes of testing, a small difference was observed between the products whose MIC was the same. Polymer A showed a lower pressure differential than the phosphonate (0.56 for the polymer and 0.90 for the phosphonate).

Below are summarized the minimum dosages of each product, considering all performance tests carried out: static and dynamic efficiency.

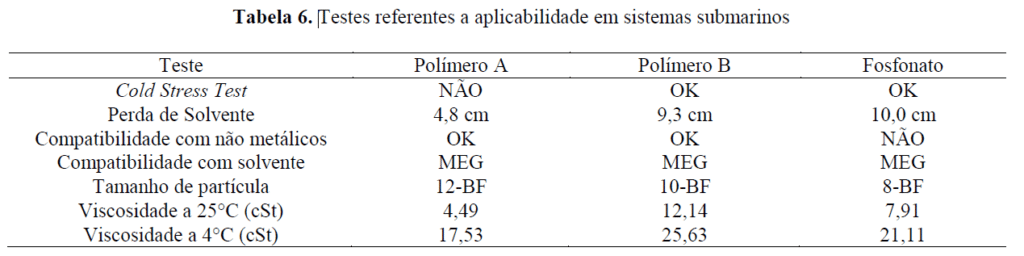

Subsea Injection Protocol

The three products were subjected to tests related to the subsea injection protocol. The tests performed and the results obtained are summarized in the table below:

The Cold Stress Test is a long-duration test (7 days) in which the product is subjected to low temperatures (4°C) and a centrifugal acceleration of 1,000 g. The aim is to verify whether the product shows any precipitation, gel formation, phase separation, or other significant visual modification. Polymer B and the phosphonate showed no apparent modification after the test. Polymer A, after 7 days, showed the formation of small clumps on the upper part of the product. This behavior indicates that the product is not recommended for subsea application.

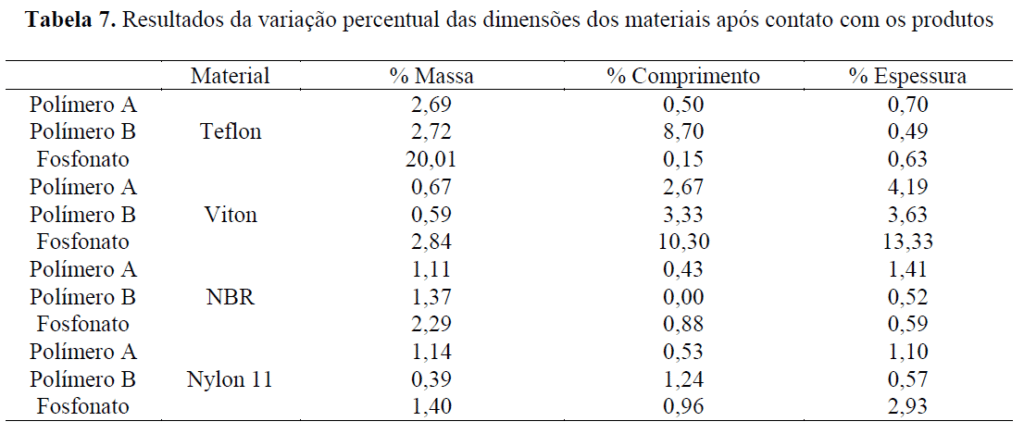

The solvent loss test aims to identify possible problems related to column collapse. For this purpose, the product is subjected for 8 days at 80°C in a U-shaped glass tube. After the test, the product must not show any precipitation, phase separation, or gel formation. After testing, only a natural solvent loss due to the high temperature to which the products were subjected was evidenced.

Compatibility tests with nonmetallic elastomers and thermoplastics were carried out at 80°C, where the material specimens were immersed in the product under evaluation for one week. For thermoplastic products (Teflon and nylon), the acceptance criterion is a variation of at most 5%, and for elastomers (NBR and Viton), this maximum variation is 10%. For both Polymer A and Polymer B, the values found were within acceptance limits. For the phosphonate product, the values were out of limits for Teflon and Viton, and its application in units that have these materials as structural components is therefore not recommended.

Product compatibility with solvents is assessed to determine which solvent is most suitable for umbilical cleaning. Products and solvents are mixed at ratios of 9:1, 1:1, and 1:9, and a visual evaluation is made to ensure there is no turbidity, precipitate formation, or sludge. The scale inhibitors tested in this study were all compatible only with MEG; with ethanol, the products began to show some degree of active precipitation (turbidity) at certain ratios.

Conclusions

After the study carried out with three different product classes under different brine conditions with different scaling tendencies, it was possible to observe that each active has a different particularity.

For the phosphonate, it was observed that it shows poor compatibility compared with polymeric materials. On the other hand, in general, it has higher efficiency than the other bases tested, as its MIC was lower. Regarding its applicability in subsea systems, its caveats regarding compatibility with elastomers and thermoplastics must be observed.

Polymers A and B present similar compatibility (across the entire range tested), but they can be differentiated with respect to performance and subsea protocol tests. In brines whose scaling tendency is related to calcium carbonate salts (such as Brine 3, for example), greater effectiveness of the sulfonated copolymer (Polymer A) can be verified compared with the sulfonated terpolymer (Polymer B). This behavior can be explained by the different adsorption interactions between the polymeric actives (with different structures) and the active sites of the crystals. As for the complementary applicability tests, it should be noted that the terpolymer shows an advantage with regard to forced low-temperature precipitation tests (Cold Stress Test) and particle size. For this reason, when recommending a product for a given application, the sum of all results involved should be evaluated to make the best choice for each application.

Referências

1- PENG, Y., SHI, L., FAN, C. Combination Package Development of Scale Inhibitors and Hydrogen Sulfide Scavengers for Sour Gas Production in Barnett ShaleSoc. of Petrol. Eng. SPE-174018-MS, 2015.

2- MONTGOMERIE, H. Novel Inhibition Chemistry for Oilfield Scale Management. University of Huddersfield, 2014. 3- FURUNCUOGLU, T., UGUR, I. Role of Chain Transfer Agents in Free Radical Polymerization Kinetics.Macromol.,4,43, p. 1823-1835, 2010.

4- ZHANG, Q. Z. Molecular simulation of oligomer inhibitor for calcite scale. Particuology, 10, p. 266-275, 2012.

5- DYER, S. J., GRAHAM, G. M., The effect of temperature and pressure on oilfield scale formation. Journ. Petrol. Sci. Eng., 35, p. 95-107, 2002.

6- GUICAI, Z., ZHAOZHENG S. Investigation of scale inhibitor mechanisms based on effect of scale inhibitor on calcium carbonate crystal form. Sci. China Ser. B – Chem., 1, 50, p. 114 – 120, 2007.

7- RODRIGUES, K. A., SANDERS, J. Sulfonated Graft Copolymers, 24, Un. Sta. Pat. App, 0020948 A1, 2008. 8- KIMBERLEY, E. Traceable polymeric sulfonate scale inhibitors and methods of using, WO 2014055343 A1, 2014.

Source: IBP1556_16

___________________________________________________

___________________________________________________