Gabriela Feix Pereira ¹, ²; Bibiana Braga ¹; Gertrudes Corção 2

1 DORF KETAL BRASIL LTDA., P&D, Nova Santa Rita, RS – Brasil. 2 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Departamento de Microbiologia, Porto Alegre, RS – Brasil.

(1) Introduction

During oil extraction and production, water-related processes are prone to microbial growth. Uncontrolled proliferation of these microorganisms can lead to serious issues, such as corrosion of metallic structures, biofilm formation, and the production of harmful metabolic byproducts like hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). In addition to posing health and safety risks, H₂S can negatively affect the quality of the extracted oil.

The primary source of water in oil extraction and production is produced water, which is extracted from the well along with crude oil as an emulsion. On the platform, this emulsion is separated, and the produced water undergoes treatment until it meets the standards for discharge or reinjection back into the well. Produced water has a complex and variable physicochemical composition, which supports a diverse microbial population (Al-Ghouti et al., 2019).

Alongside the variable composition of produced water, the extreme conditions during extraction and production—such as high temperatures, low oxygen levels, and high salinity—favor the survival of particularly adapted microorganisms. Commonly found groups in the produced water microbiome include Acid-Producing Bacteria (APB) and Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (SRB) (Li et al., 2017). Under oxygen-depleted or anoxic conditions, APB can produce various organic and inorganic acids through fermentative metabolism, which lowers the pH of the water. This change can impact electrochemical reactions and increase the corrosion rate of the system. Meanwhile, SRB can generate H₂S through cellular respiration in the presence of sulfate or other sulfur sources, also occurring under oxygen-depleted conditions. H₂S is a toxic, corrosive, and flammable gas, representing a significant concern in the oil industry.

Given this background, the objective of this study was to evaluate the differences in microbiome composition between two produced water samples (PW 1 and PW 2) collected from geographically distant Brazilian oilfields. Additionally, the effect of biocides on reducing the concentrations of APB and SRB in these produced water samples was assessed. Tetrakis(hydroxymethyl) phosphonium sulfate (THPS) and glutaraldehyde, both widely used in the microbiological treatment of produced water, were the biocides tested (Kahrilas et al., 2015; Korenblum et al., 2010).

(2) Materials and Methods

(2.1) Produced Water Samples

Two produced water samples were used in this study. Sample PW1 was collected from an offshore oilfield in southeastern Brazil, while Sample PW2 was collected from an onshore oilfield in northeastern Brazil. The samples were kept refrigerated and filtered through 0.22 µm filters within 72 hours. The filters that retained microorganisms were stored at -20°C until analysis.

(2.2) Analysis of Bacterial Composition of Produced Water Samples

(2.2.1) DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from the samples in duplicate using the DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the extracted DNA from each sample was measured using a Quantus fluorometer (Promega, USA) with the dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Invitrogen, USA).

(2.2.2) Amplification and Sequencing of the 16S rRNA Gene

The V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the primers 515F (5´ GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA 3´) and R806 (5´ GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT 3’), both of which were modified to include an Illumina adapter region (Caporaso et al., 2011). PCR amplification was performed using a mixture containing approximately 100 ng of genomic DNA, 1.0 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 µM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 2 U of Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Life Technologies, USA), and 1× reaction buffer. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation for 2 minutes at 94°C, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (45 seconds at 94°C), annealing (45 seconds at 55°C), and extension (1 minute at 72°C), ending with a final extension of 6 minutes at 72°C, using a Mastercycler Personal 5332 Thermocycler (Eppendorf, Germany).

Following amplification, amplicons were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Inc., USA) using a v2 500 kit, generating 250 bp reads. The sequencing data were processed using the QIIME 2 software package (Hassan et al., 2018), and all statistical analyses were conducted using Python scripts implemented within QIIME 2. After clustering operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity, mapping was performed against the RDP database (Wang et al., 2007). The metagenomic sequence data are available at the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) under accession number ERP121357 in the EBI Metagenomics database.

(2.3) Culture of APB and SRB from Produced Water Samples

APB and SRB cultures from produced water samples were enriched for 21 days at 35°C. Both cultures were transferred weekly, using 10% inoculum, to sterile culture media. For the APB culture, Phenol Red Broth medium with glucose (15 g·L⁻¹; Merck, Germany) was utilized. For the SRB culture, a modified Postgate B medium (McKenzie & Hamilton, 1992; Postgate, 1984) was employed. Before use, the media were purged with nitrogen (N₂) to decrease the oxygen content.

(2.4) Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Biocides in APB and SRB Cultures

To evaluate the resistance of APB and SRB cultures to glutaraldehyde and THPS, the MIC of each biocide was determined. A 1% (v/v) inoculum and different biocide concentrations (50 to 1,000 mg·L⁻¹) were added to 96-well microplates containing 200 µL of culture medium (Schug et al., 2020). For test validation, a positive control of each culture without biocide was used. The analysis was performed in triplicate. Microtiter plates were incubated in an anaerobic jar containing an anaerobiosis generator (Anaerobac, Probac, Brazil) for 72 h at 35°C.

(3) Results and Discussion

(3.1) Bacterial Composition of Produced Water Samples

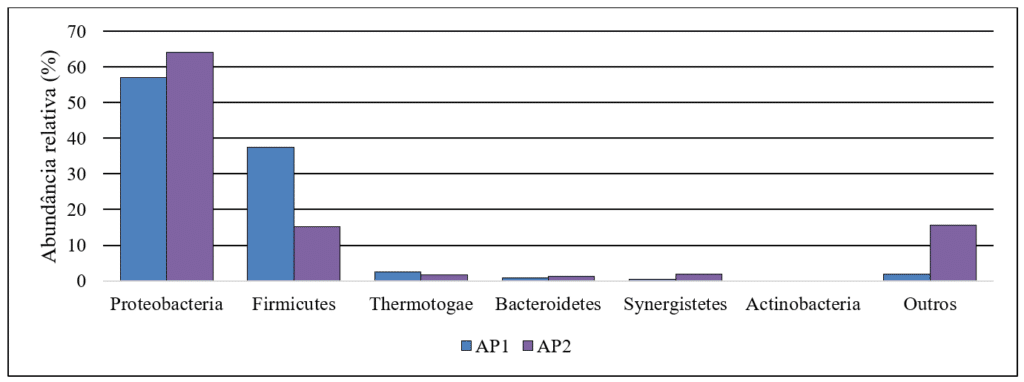

The composition of the microbiome in produced water, along with its physicochemical characteristics, can vary significantly. However, certain bacterial phyla are commonly found in these samples. Generally, the predominant phylum is Proteobacteria, which is widely distributed in oilfield ecosystems. This is followed by Firmicutes, Defferibacteres, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Thermotogae (Li et al., 2017). In this study, Figure 1 illustrates the relative abundance of the bacterial phyla found in the analyzed samples. The distribution profile of phylum abundance observed is consistent with findings in the literature regarding other analyzed produced water samples. This trend may be attributed to the extreme conditions typically present in oilfields, such as the presence of hydrocarbons, high salinity, and elevated temperatures. These harsh environments often favor the survival of the most adapted microorganisms; however, significant differences are generally more apparent at the order and genus levels.

Figure 1 – Relative abundance of bacterial phyla in produced water samples.

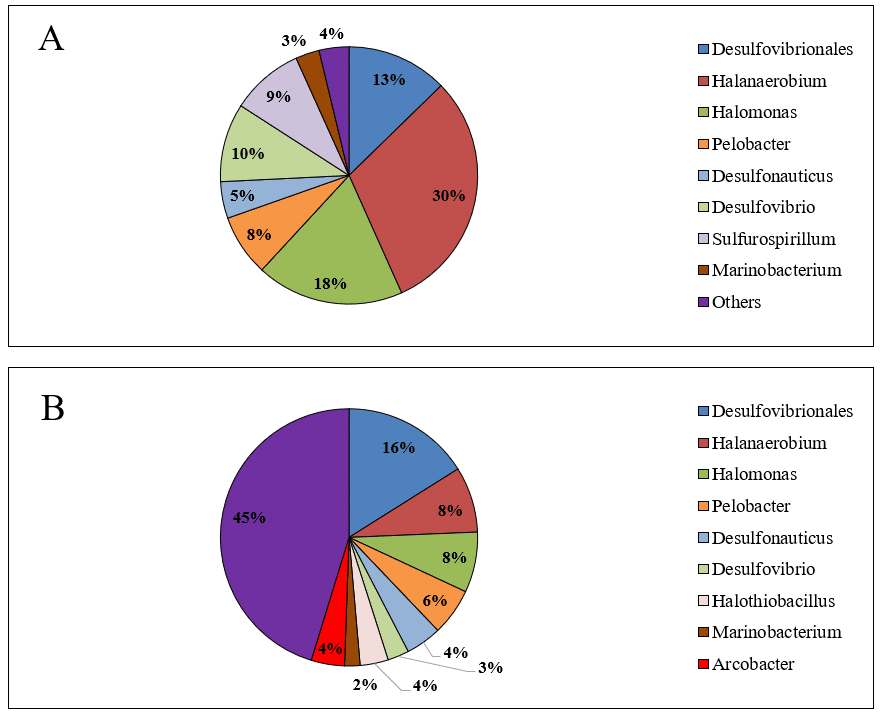

The composition of bacterial genera varied significantly between the produced water samples (Figures 2A and 2B), unlike that of phyla. Furthermore, the genus diversity in the PW2 microbiome was greater than in PW1. Another notable observation is the high abundance of unknown genera in the PW2 sample, which accounted for 45%. The increased bacterial diversity and the predominance of unidentified bacterial genera in PW2 may impact the effectiveness of biocide treatments in onshore oilfields.

Figure 2 – Relative abundance of bacterial genera in produced water samples PW1 (A) and PW2 (B).

The samples analyzed in this study revealed a significant presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) belonging to the order Desulfovibrionales. These bacteria were divided among the genus Desulfovibrio, other unidentified genera, and the genus Desulfonauticus. Each sample exhibited a unique abundance profile among the different phyla and genera, with the total relative abundance of SRB being 28% in PW1 and 23% in PW2. SRB thrive in environments with sulfate, which they utilize as an electron acceptor in the dissimilatory sulfate reduction pathway for energy generation (Muyzer & Stams, 2008; Qian et al., 2019). Although sulfate was detected in the samples (3,314 mg·L⁻¹ in PW1 and 692 mg·L⁻¹ in PW2), this was not the only factor influencing SRB composition. Other factors, including temperature, salinity, and bacterial competition, also played a role in the abundance of these bacteria (Li et al., 2017).

Furthermore, the samples revealed a notable prevalence of halophilic and halotolerant anaerobic phototrophic bacteria (APB) groups, such as Halanaerobium and Halomonas, which are typically found in produced water due to hypersaline conditions. Halanaerobium was particularly dominant in PW1, accounting for 30% of the relative abundance (Figure 2A). This genus consists of obligate anaerobic and moderately halophilic bacteria that require NaCl concentrations between 30,000 and 200,000 mg·L⁻¹ for their growth (Oren, 2014). Halanaerobium species are known for their role in thiosulfate reduction and have been implicated in the corrosion of carbon steel, which is commonly used in tanks, pipelines, and other infrastructures (Liang et al., 2014). A study evaluating the susceptibility of Halanaerobium DL-01 to biocides found that high concentrations of glutaraldehyde (500 mg·L⁻¹) and THPS (approximately 406 mg·L⁻¹) were necessary to inhibit its growth (Liang et al., 2016).

The genus Pelobacter, also commonly found in produced water, consists of strictly anaerobic, gram-negative bacteria that cannot ferment sugars and have a limited range of substrates for metabolism. Pelobacter species play essential roles in the fermentative degradation of less common substrates such as ethanol and butanol, and they can utilize elemental sulfur (S°) as an electron acceptor in these processes (Sun et al., 2010). Additionally, studies have shown that Pelobacter species are associated with methanogenic bacteria in the degradation of crude oil alkanes (Gray et al., 2011).

Unidentified bacteria classified as “other” were present in varying proportions in both samples. In sample PW1, only 4% of the bacteria were unidentified, while sample PW2 contained a significantly higher proportion of 45%. The complex metagenome and the extreme, unique conditions of oil fields may account for the high prevalence of unidentified bacteria.

(3.2) Resistance of SRB and APB Cultures to Biocides

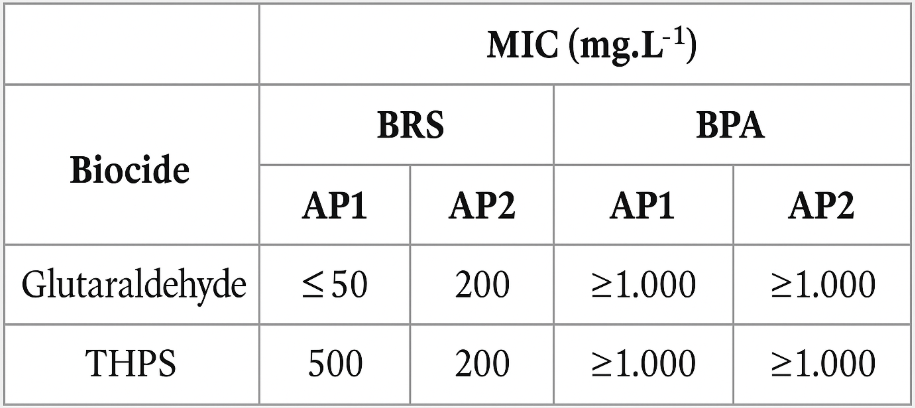

APB and SRB cultures were utilized to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of glutaraldehyde and THPS. The results of this evaluation are presented in Table 1. The responses of the SRB cultures to the biocides varied, with glutaraldehyde exhibiting a lower MIC in PW1 and THPS showing a lower MIC in PW2. In contrast, APB cultures required high concentrations of both biocides (above 1,000 mg·L⁻¹) to achieve growth inhibition, indicating a significant level of resistance to these compounds when used individually.

Table 1 – MIC of glutaraldehyde and THPS in SRB and APB cultures derived from produced water samples.

The varying resistance levels found in bacterial cultures from different origins highlight the necessity for individualized analysis to determine the most effective microbiological treatment.

(4) Final Considerations

Research on the bacterial composition in oilfields and its effects in various contexts has evolved over the years. However, the interactions between bacterial populations and their resistance to biocides remain inadequately understood. This study found that, despite varying abundances among samples, the sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and acid-producing bacteria (APB) groups were predominant. Both of these groups are known to contribute to corrosion of metallic structures, biofilm formation, and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) generation (Li et al., 2017). Consequently, it can be concluded that the analyzed samples pose a significant risk of damage to production facilities.

The responses of SRB and APB cultures to biocides varied, underscoring the need for tailored treatment strategies that account for the local bacterial population’s resistance levels to the biocides used. Additionally, other approaches can improve the effectiveness of microbiological treatments. These include using multiple biocides with different modes of action, which can expand the antimicrobial spectrum and decrease bacterial resistance, along with ongoing monitoring of the treatment to adjust dosages and assess performance.

(5) References

Al-Ghouti, M. A., Al-Kaabi, M. A., Ashfaq, M. Y., & Da’na, D. A. (2019). Produced water characteristics, treatment and reuse: A review. In Journal of Water Process Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.02.001

Caporaso, J. G., Lauber, C. L., Walters, W. A., Berg-Lyons, D., Lozupone, C. A., Turnbaugh, P. J., Fierer, N., & Knight, R. (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(Supplement 1), 4516–4522. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000080107

Gray, N. D., Sherry, A., Grant, R. J., Rowan, A. K., Hubert, C. R. J., Callbeck, C. M., Aitken, C. M., Jones, D. M., Adams, J. J., Larter, S. R., & Head, I. M. (2011). The quantitative significance of Syntrophaceae and syntrophic partnerships in methanogenic degradation of crude oil alkanes. Environmental Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02570.x

Hassan, M., Essam, T., & Megahed, S. (2018). Illumina sequencing and assessment of new cost-efficient protocol for metagenomic-DNA extraction from environmental water samples. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjm.2018.03.002

Kahrilas, G. A., Blotevogel, J., Stewart, P. S., & Borch, T. (2015). Biocides in Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids: A Critical Review of Their Usage, Mobility, Degradation, and Toxicity. Environmental Science & Technology, 49(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1021/es503724k

Korenblum, E., Valoni, É., Penna, M., & Seldin, L. (2010). Bacterial diversity in water injection systems of Brazilian offshore oil platforms. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 85(3), 791–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-009-2281-4

Li, X. X., Mbadinga, S. M., Liu, J. F., Zhou, L., Yang, S. Z., Gu, J. D., & Mu, B. Z. (2017). Microbiota and their affiliation with physiochemical characteristics of different subsurface petroleum reservoirs. In International Biodeterioration and Biodegradation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2017.02.005

Liang, R., Davidova, I. A., Marks, C. R., Stamps, B. W., Harriman, B. H., Stevenson, B. S., Duncan, K. E., & Suflita, J. M. (2016). Metabolic Capability of a Predominant Halanaerobium sp. in Hydraulically Fractured Gas Wells and Its Implication in Pipeline Corrosion. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 988. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00988

Liang, R., Grizzle, R., Duncan, K., McInerney, M., & Suflita, J. (2014). Roles of thermophilic thiosulfate-reducing bacteria and methanogenic archaea in the biocorrosion of oil pipelines. Frontiers in Microbiology, 5, 89. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00089

McKenzie, J., & Hamilton, W. A. (1992). The assay of in-situ activities of sulphate-reducing bacteria in a laboratory marine corrosion model. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 29(3–4), 285–297.

Muyzer, G., & Stams, A. J. M. (2008). The ecology and biotechnology of sulphate-reducing bacteria. In Nature Reviews Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1892

Oren, A. (2014). The Order Halanaerobiales, and the Families Halanaerobiaceae and Halobacteroidaceae. In E. Rosenberg, E. F. DeLong, S. Lory, E. Stackebrandt, & F. Thompson (Eds.), The Prokaryotes: Firmicutes and Tenericutes (pp. 153–177). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-30120-9_218

Postgate, J. R. (1984). The Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Qian, Z., Tianwei, H., Mackey, H. R., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M., & Guanghao, C. (2019). Recent advances in dissimilatory sulfate reduction: From metabolic study to application. In Water Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.11.018

Schug, A. R., Bartel, A., Scholtzek, A. D., Meurer, M., Brombach, J., Hensel, V., Fanning, S., Schwarz, S., & Feßler, A. T. (2020). Biocide susceptibility testing of bacteria: Development of a broth microdilution method. Veterinary Microbiology, 248, 108791. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2020.108791

Sun, J., Haveman, S. A., Bui, O., Fahland, T. R., & Lovley, D. R. (2010). Constraint-based modeling analysis of the metabolism of two Pelobacter species. BMC Systems Biology. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-0509-4-174

Vigneron, A., Alsop, E. B., Lomans, B. P., Kyrpides, N. C., Head, I. M., & Tsesmetzis, N. (2017). Succession in the petroleum reservoir microbiome through an oil field production lifecycle. ISME Journal. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.78

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M., & Cole, J. R. (2007). Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00062-07