Regulations on carbon emissions make refinery operation more expensive, but proper treatment and monitoring with antifoulants can substantially reduce these costs.

The United Nations Kyoto Protocol established the first binding targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in 1997. Although the U.S. and China declined to participate, 37 industrialized countries and the European Union (EU) now regulate carbon emissions, and the trend appears clear. The EU Energy Pact aimed for a 20% reduction in CO₂ emissions by 2020, and a carbon pricing scheme was already implemented in Australia in 2013.

These are challenging times for refineries. Sulfur levels in finished fuels must be reduced to meet increasingly stringent specifications driven by new emission control technologies in motor vehicles. Meanwhile, crude oil feedstocks are becoming heavier, higher in sulfur, and more difficult (and energy-intensive) to process.

Refineries are significant sources of carbon emissions, largely in the form of CO₂ from fuel combustion to distill, crack, and hydro-treat their feedstocks. Despite limits and taxes imposed on carbon, demand for refinery products continues to grow, increasing refinery energy use and emissions. Heavier and more acidic crude feedstocks further aggravate the problem.

The costs are substantial: energy costs for a typical refinery account for 50–60% of total operating costs, excluding feedstocks (1). Efficiency, always a top priority in refinery operations, has never been more important—or more difficult—to achieve.

Since crude oil cost is the most important determinant of refinery profitability (2), the price differentials among challenging crudes are highly attractive, even though refinery unit designs often limit feedstock flexibility, and heavy crudes can lead to fouling problems—both of which increase carbon emissions that must be considered in the refinery’s operating cost model.

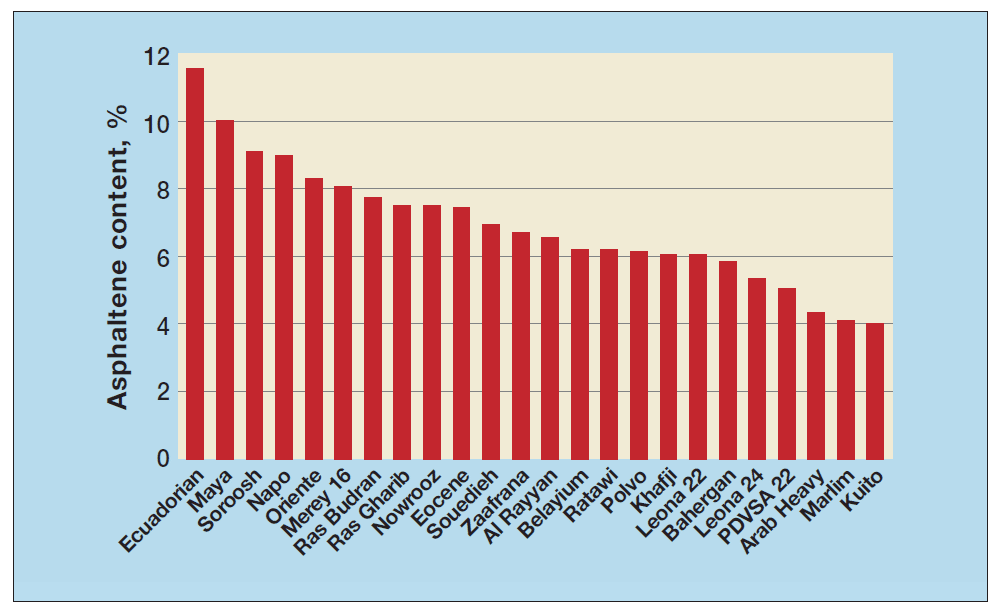

Consider the approximate current prices of Murban crude (0.6 wt% asphaltenes) and Maya crude (10.0 wt% asphaltenes). Since Maya is $13.61/bbl cheaper than Murban, a refinery processing 100,000 b/d can save up to $1,361,000 per day in feedstock costs alone. As the small sample of crudes in Figure 1 shows, Maya is just one of many common crudes rich in asphaltenes.

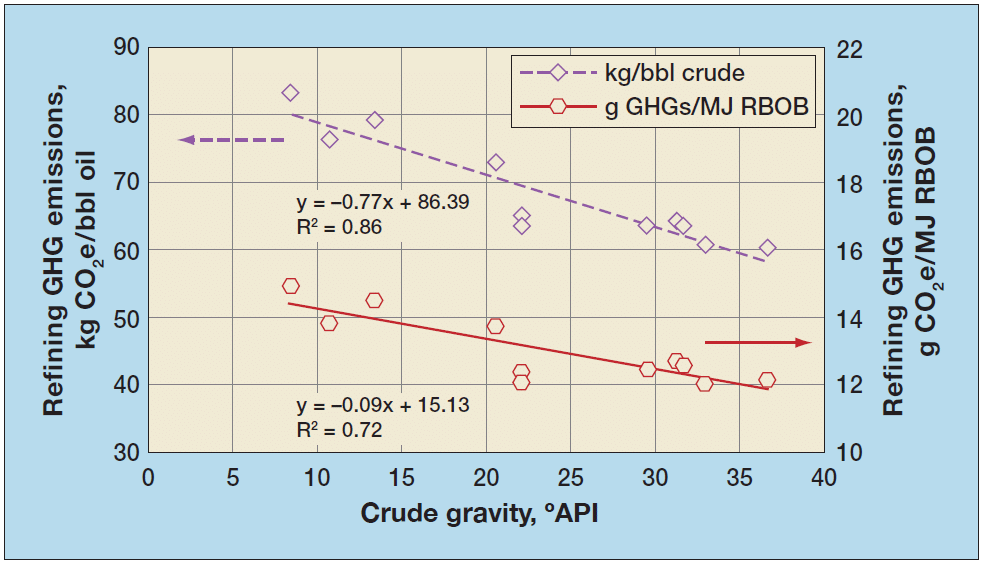

Processing these heavier, sulfur-rich crudes consumes more energy and increases greenhouse gas emissions (see Figure 2).

The calculation of actual costs can be quite complex, partly because different fuels are often used at various stages within the refinery. Fuel oil and refinery gas are common choices for refinery furnaces, and their energy content and emissions differ. Although it typically takes less refinery fuel oil to heat feedstock to the target temperature than would be the case with refinery fuel gas (refinery fuel oil has a calorific value of 8,740 kcal/m³ compared to 10,000 kcal/m³ for fuel gas), carbon emissions from fuel oil are generally higher per unit of fuel consumed.

Refinery feedstock itself is another important consideration. Crude oil production can generate enough CO₂ emissions to make a given feedstock more expensive overall. The production of bituminous shale, for example, has been shown to contribute more significantly to carbon emissions than the extraction of other hydrocarbons.

These issues are becoming increasingly important because of how carbon emission regulations work. The Western Climate Initiative, in selected Canadian provinces and California, is running a cap-and-trade program. In Europe, the EU Energy Pact targets key goals, particularly a 20% reduction in CO₂ emissions (relative to 1990 levels), aiming to ensure that at least 20% of total energy consumption comes from renewable sources.

Emissions Trading Scheme

To meet these new targets, many countries have adopted Kyoto mechanisms such as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), through which countries can purchase carbon credits known as emission reduction units. These may be purchased from Clean Development Mechanism projects or from joint implementation carbon-reduction projects.

The European Union’s cap-and-trade regulations are the largest ETS to date. Companies receive emission allowances that they can buy, sell, or trade among themselves, but at the end of each year, each company must hold enough emission allowances to cover its total emissions.

The EU ETS regulates 46% of the EU’s CO₂ emissions, limiting the amount of CO₂ that can be emitted by factories and plants. Once Phase III (2013–2020) of the scheme is fully implemented, tighter emission controls can be expected, along with greater efforts to reduce carbon credit consumption.

Support for these schemes is not universal. Canada withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in December 2011 to avoid heavy penalties for failing to meet its emission targets. China, one of the world’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases, did not sign the Kyoto Protocol, but even there, plans are underway to launch pilot cap-and-trade markets and to establish a fully operational carbon market.

Despite these regional differences, it is clear to refiners worldwide that carbon costs are becoming a significant variable in the refinery cost equation, and many are actively seeking opportunities to reduce emissions by increasing efficiency. Their first targets are fuel-consuming systems—such as furnaces and preheaters—where efficiency depends on feedstock, fuel source, and combustion performance.

Efficiency gains achieved through feedstock changes must be weighed against the profit potential of cheaper crudes. Changing fuel types may require significant investment and can have a substantial impact on operations. Combustion enhancers are a lower-cost option that can help in some cases.

Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is another alternative. As the name suggests, CCS limits the amount of CO₂ released into the atmosphere by capturing CO₂ and storing it in underground geological formations. This too is capital-intensive. CCS is the way of the future, despite its economic implications.

Antifoulants

Antifoulants offer another way to improve efficiency—a proven approach that requires little or no capital investment. Antifoulants can also enhance gross margins by increasing refinery feedstock flexibility, and their costs are generally very low compared to alternatives.

Uncontrolled fouling decreases heat-transfer efficiency and yield, increasing fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Feedstock flexibility is impaired, and if untreated, fouling reduces throughput and can force units to shut down for cleaning or repair.

Fouling is generally of two types: inorganic and organic. The former is usually caused by elevated metal levels in refinery feedstocks, typically occurs between 150°C and 360°C, and tends to increase the potential for costly and dangerous corrosion. Crudes produced in deep-water offshore locations often exhibit inorganic fouling due to contaminants such as salts, filterable solids, basic sediments, and corrosion products.

Organic fouling generally occurs above 250°C in cracked streams, often as a result of high asphaltene content or incompatible blends of asphaltenic and paraffinic crudes. Whether the fouling is inorganic or organic, success with antifoulants depends on careful monitoring. Key parameters include heat-transfer rates, heat-exchanger duties, approach enthalpies, feedstock composition, CO₂ emissions, and fuel-combustion efficiency.

Antifoulant selection is also important, especially with today’s increasingly acidic feedstocks. Sulfidation is common with these crudes, leading to iron-sulfide-promoted fouling. In most cases, antifoulants must therefore be effective against both asphaltenes and iron sulfide.

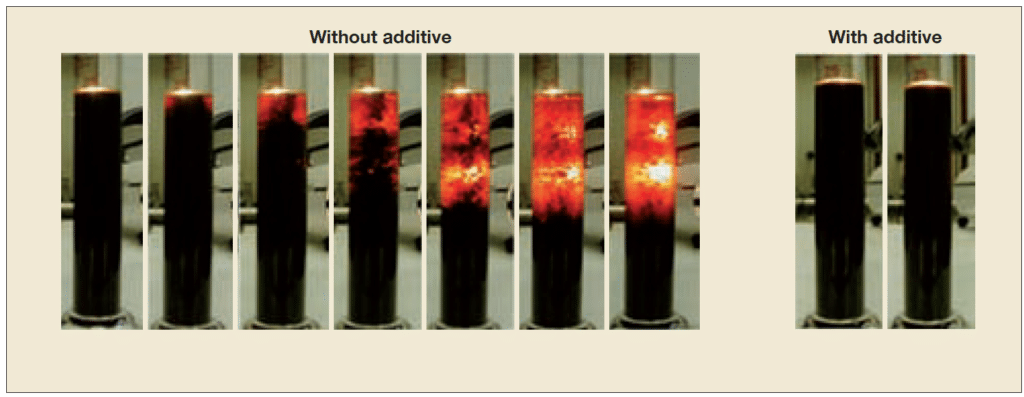

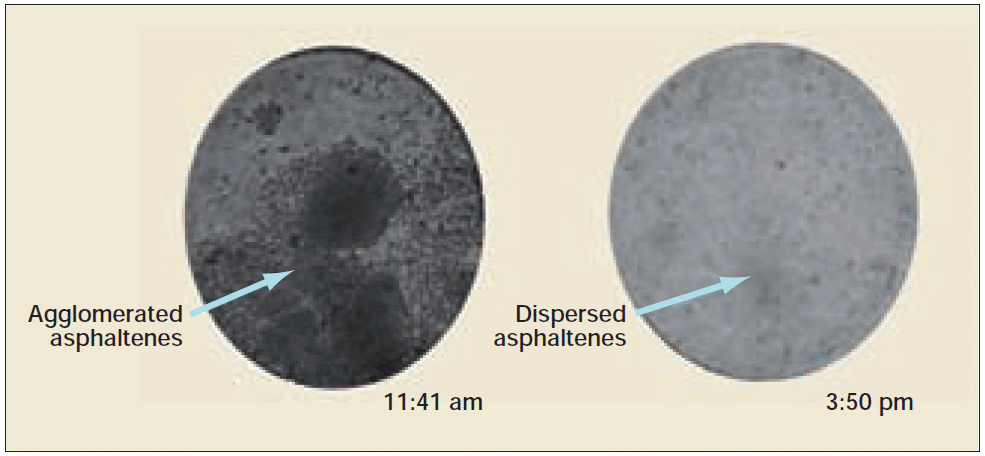

Antifoulants work by stabilizing asphaltenes that would otherwise become unstable when heated. This prevents the deposition of polynuclear aromatics, which, when further heated, can form coke. If left uncontrolled, fouling reduces heat transfer from the heating medium to the cold stream and increases the furnace duty required to achieve the target coil outlet temperature (COT). Figures 3 and 4 illustrate antifoulant functionality, comparing untreated feedstock with treated samples. Asphaltenes that agglomerate and deposit within minutes without antifoulant treatment remained stabilized for an hour or more in testing.

Experience indicates that antifoulants can increase furnace inlet temperature by 5–15°C in fouled systems. Even greater improvements are possible with periodic cleaning.

The way an antifoulant is applied has a considerable influence on results, and choosing the correct injection point is especially important. A suction pump upstream of the main fouling exchangers is ideal.

Case Study

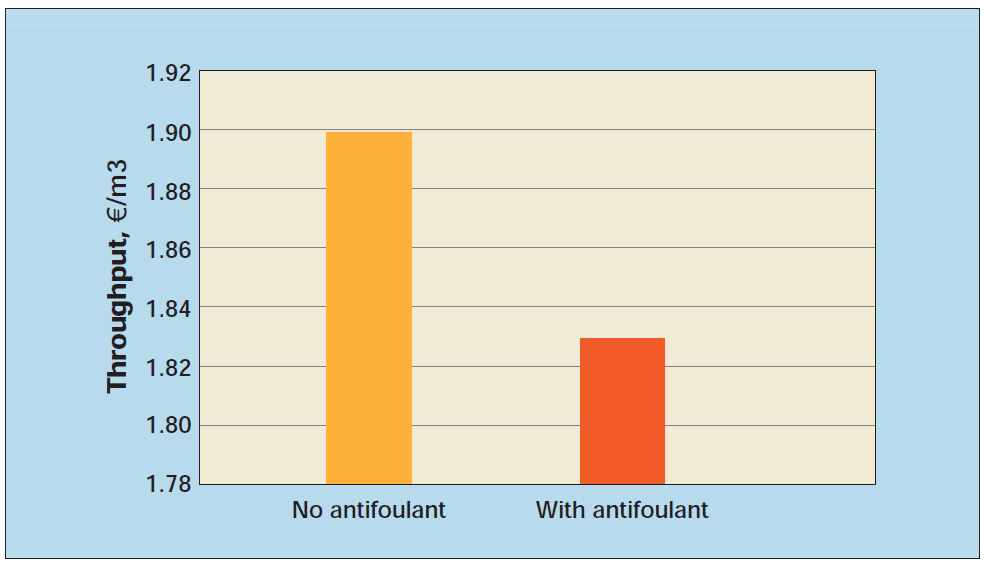

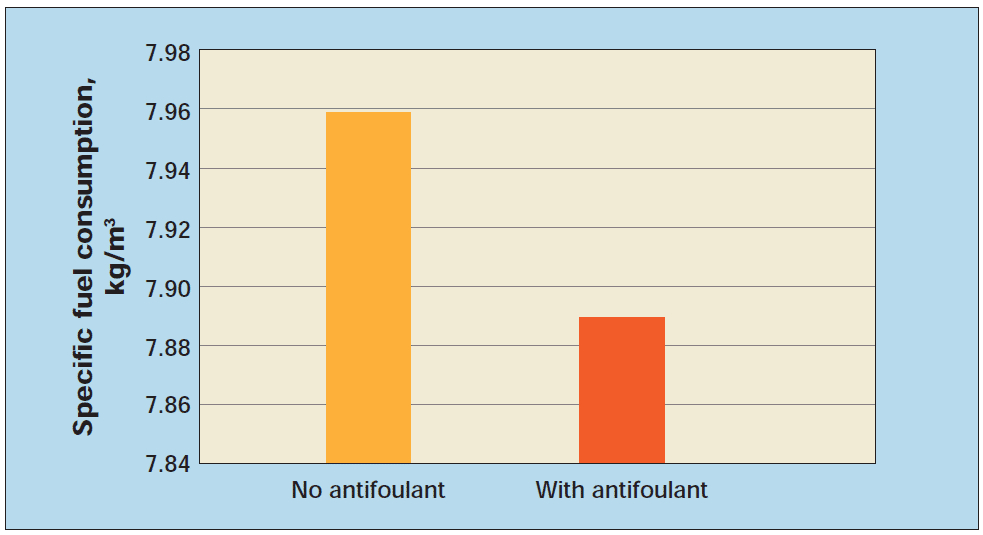

The following case study illustrates the potential benefits of antifoulants in reducing fuel costs and CO₂ emissions. Refinery X was operating with an average throughput of more than 300,000 b/d. The average coil outlet temperature (COT) when the feedstock was treated with antifoulants met the refinery standard required to produce target yields of finished downstream products. Without antifoulant treatment, the target COT was often impossible to reach, and much more energy was required (see Figure 5).

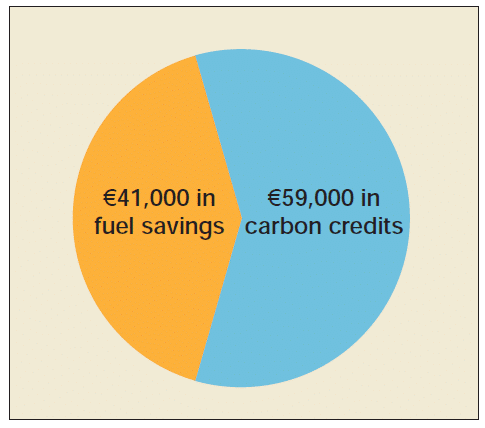

Antifoulant treatment significantly reduced the fuel consumption required to maintain the target COT, lowering the specific fuel costs by nearly 4% (see Figure 6). This saved the refinery approximately €41,000 per month in fuel alone.

With an average carbon credit value of €16 per metric ton of CO₂, the refinery’s carbon cost savings would total €59,000, increasing the overall financial impact of antifoulant treatment to approximately €100,000 per month (see Figure 7).

Conclusions

Regulations on carbon emissions make refinery operation more expensive, but it has been demonstrated that proper treatment and monitoring with antifoulants can substantially reduce these costs.

Antifoulants also enable refiners to improve gross refining margins by processing lower-cost feedstocks. They reduce the amount of fuel required to maintain coil outlet temperatures for target yield rates. Overall, antifoulants are an environmentally responsible choice with attractive economic benefits.

Experience indicates that antifoulants can increase furnace inlet temperature by 5 to 15°C in fouled systems. Even better performance is possible with periodic cleaning. The method of antifoulant application has a considerable influence on results, and choosing the correct injection point is especially important. A suction pump located upstream of the main fouling exchangers is ideal.

References

(1) Based on a natural gas price of about $6/MM Btu for a typical 100 KBPSD refinery that emits 1.2-1.5 MM t/yr of CO2.

(2) Stockle M, Carter D, Jones L, Optimising Refinery CO2 Emissions, Foster Wheeler Technical Paper www.fwc.com/publications/ tech_papers/files/ERTC%20CO2%20paper%2 0Nov07.pdf

(3) Brandt A R, Unnasch S, Energy intensity and greenhouse gas emissions from California thermal enhanced oil recovery, Energy & Fuels 2010: Keesom W, Unnasch S, Moretta J, Life cycle assessment comparison of North American and imported crudes. Technical report, Jacobs Consultancy and Life Cycle Associates for Alberta Energy Resources Institute, 2009.

____________________________________

Authors

India Nagi-Hanspal — MEng in Chemical Engineering from Imperial College London.

Mahesh Subramaniyam — Director of Research & Development at Dorf Ketal Chemicals. PhD in Chemistry from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai.

Parag Shah — Global Technical Services Division Leader for Refineries at Dorf Ketal Chemicals. Specialist in software development for desalter fitness testing and fouling monitoring in preheat exchanger trains. BEng in Chemical Engineering from the University of Mumbai.

James Noland — BEng in Chemical Engineering from Mississippi State University, USA.